Up until 2 months ago, I hadn't thought much about anti-phishing since I left my Netcraft job in 2017. Then Martin and I did a short consulting gig for another anti-phishing company, and I've been consumed by anti-phishing ever since.

Specifically, I'm looking at anticloaking.

"Cloaking" is when a phishing site takes steps to hide itself from the Internet security companies. They can block specific IP addresses, block based on geolocation, or potentially do more complex things based on browser User-Agent strings, and so on. A human user might click a link to a phishing site and see their bank's login page, while a bot gets a harmless 404 page.

Anticloaking is the defence against cloaking.

Obviously there is an arms race here. The threat intelligence companies get better at anticloaking, the phishing sites get better at cloaking. It's the circle of life.

For most of the time that I worked in anti-phishing, headless browsers basically didn't exist. There were ways to run JavaScript code if you worked hard at it, but stitching everything up to look like a real browser was a lot of trouble.

Running JavaScript is mandatory, because otherwise you're defeated by an empty page that uses <script> tags to load the phishing content. Unfortunately, when you let the site run JavaScript you leak a lot more signal that can identify you as a bot.

These days if you just run chrome --headless you are 80% of the way there. The remaining 20% is where all the interesting stuff is.

We've setup a Mojolicious web server that serves a "fake phishing site", that doesn't impersonate any company in particular, and records every request it receives, and ships JavaScript code that inspects the runtime environment and sends all of the information back to the server.

We then register certificates for unique domains on this web server with LetsEncrypt (to populate CT logs), and submit to VirusTotal, and others, to provoke bot traffic.

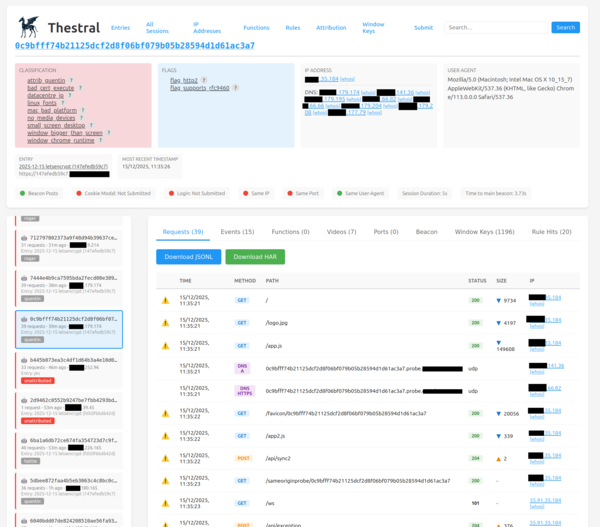

Offline we have another process constantly looking at new sessions and classifying them as "bot or not" based on (currently) 183 different rules, and we have a viewer app for viewing, searching, and filtering the collected information, to help with developing new rules and discovering new information.

You could think of it as "threat intelligence intelligence".

Here's a lightly-redacted example of a session that hit a few rules:

(ChatGPT told me that a Thestral is a creature that can see through invisibility cloaks; this turned out to be a lie).

You learn a lot of interesting things.

It turns out that every security vendor we've yet observed has major flaws in their headless browser setup which mean it's worryingly easy to cloak from them. Anything that a normal human phishing victim's browser would not do is a potential bot signal.

We've seen fake mobile phone APIs being injected into the DOM, and have been able to read out the source code implementing them. We've seen lots of people running the browser with TLS validation and same-origin policy disabled. And we've even seen people running services on localhost with CORS headers that allow cross-origin requests, allowing us to read out their server headers and page contents and which would allow us to send arbitrary requests to their local servers. We've seen people using proxies that don't support websockets. We've even seen well-known companies scanning us from netblocks that just straightforwardly name the company, which would be trivial to block by IP address.

In many cases we are able to identify the exact company that has scanned the site, but in the majority of cases we are not. It would be good to get better at this because it would inform who we should be trying to sell to. The screenshot above is attributed to "quentin", which is a name for a cluster of sessions that all behave the same, but we don't yet know which company operates this bot.

It would also be good to get better data on real human user sessions. It's actually harder to get good data on what human sessions look like than bots, because it's so easy to get bots to scan the site.

There are a few angles for monetisation. We could:

- have the customer's bot visit our page, and then tell them all the things they are doing wrong based on our existing rules

- do "pentesting for headless browsers": using the existing tooling & also by thinking hard, we find new ways to tell your headless browser is headless, and specific fingerprints that identify your bot in particular

- provide a broad-strokes report of all of the things people are doing wrong across the industry

- provide direct access to our tooling

More broadly, there are applications of this technology beyond anti-phishing. I was told that if we say it's for anti-phishing then we have 12 customers max but if it's for AI browser agents then someone will give us a billion dollars.

I would be interested in helping people do web scraping. So the proposition there would be similar as for anti-phishing (we tell you why your bot is getting blocked). I'm not really keen on doing the other side (i.e. providing a supercharged version of reCAPTCHA or whatever), because I don't think we should be building the apartheid web.

There are also different tradeoffs for the CAPTCHA side of things depending on what you're trying to do. If you're hosting a phishing site then you are really keen to block all bots and you can tolerate blocking a good chunk of real humans. But if you're just a blogger and you want to block scrapers because you don't want your ideas to influence the next generation of LLMs, then you have a harder job because you really don't want to block any humans, even if they happen to have very unusual browser configuration.

If you're running a headless browser of any kind and you're interested to learn your bot's fingerprints, get in touch and we can definitely have a look.